The laboratory of IBM Research in Brazil, in partnership with University of São Paulo, has been developing AI-based reading/writing toolsfor Indigenous languages for the last 3 years in the context of the PROLIND project of the C4AI. Writing-supporting tools are essential to easier use of languages on the Internet and social media.

IBM Research has developed translators, orthographic correctors, electronic dictionaries, and word completers for Indigenous languages. These tools, developed using state-of-the-art AI/LLM technologies, have been embedded in easy-to-use mobile and web apps. The tools were developed using linguistic data (such as dictionaries) following ethical guidelines, without data collection from Indigenous groups.

WRITING ASSISTANTS

The PROLIND Project has built several prototypes of writing assistants, starting in 2023 with some initial prototypes developed for the Guarani Mbya language. In workshops with the high school students from the Tenondé-Porã community, in São Paulo City, ideas and prototypes were explored by the students. Based on the participation of the students and teachers (criticisms, comments, and observation of usage), writing assistants were evaluated and new prototypes were developed.

The image on the top of the page shows the evolution from the Guarani Mbya prototype to the three writing assistants for the Nheengatu language which were developed. The AInLI is an Internet-based writing assistant; the ACEnLI is a writing assistant developed to be used in smartphones and tables, focused on single senteces, and for everyday use; and the EInLI is an Internet-based editor aimed to be used in the writing of longer texts with multiple lines.

The ACEnLI writing assistant is going to be the first one used by the students of the Yegatu Digital project. The app was initially developed by students from Insper based on Nheengatu AInLI, using API-based tools developed by IBM Research. It borrows familiar design concepts and affordances from other mobile translation apps. However, it expands the concepts and functionalities of AInLI to a mobile scenario, to be tested and refined with speakers of the language.

TRANSLATORS TOOLS

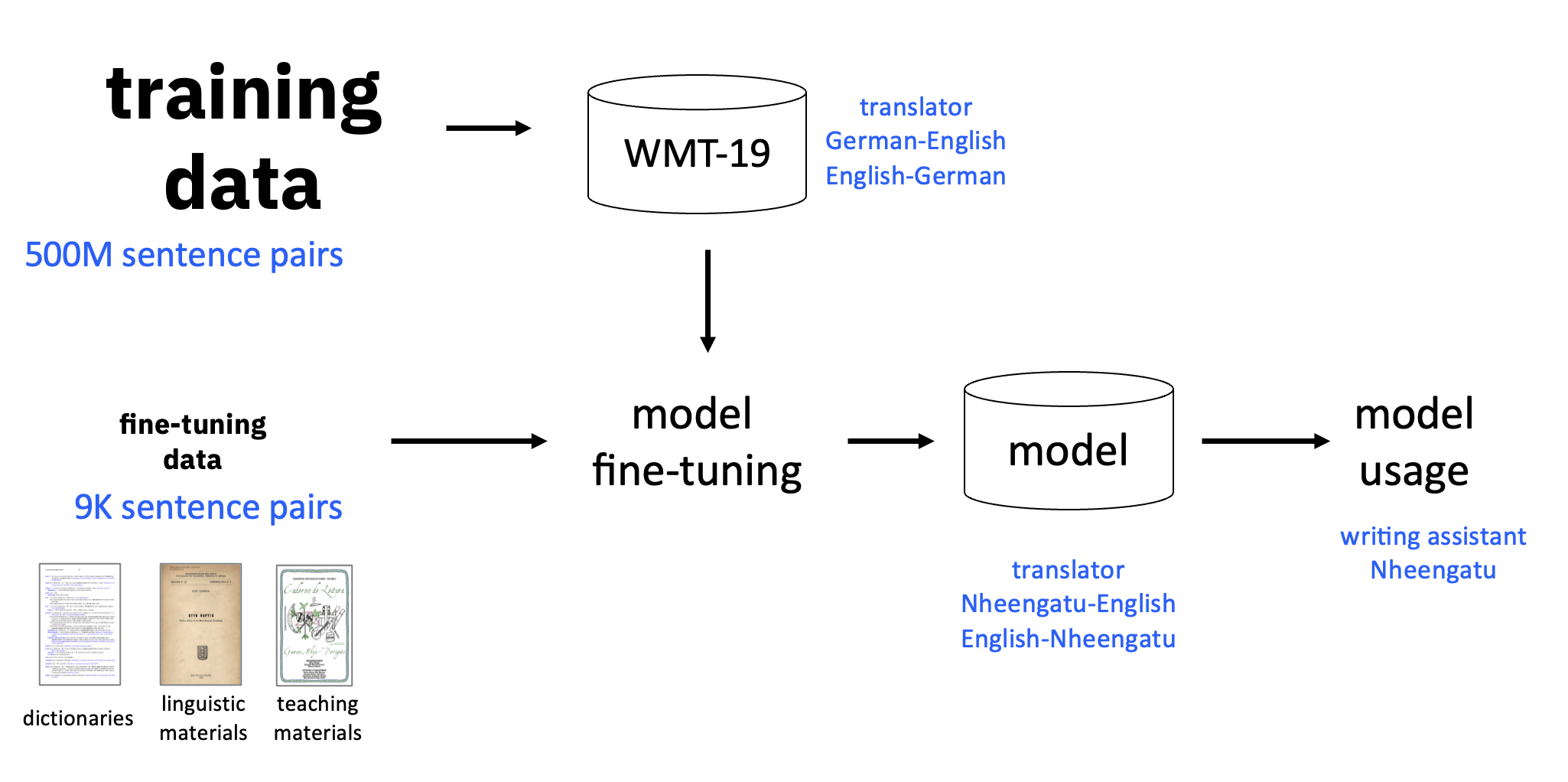

The translator tools used in the Nheengatu prototypes were built as the result of solving technical challenges and developing solutions to create bilingual machine translators (MTs) for Indigenous languages based solely on publicly available linguistic data as seen in the figure above.

Given the extremely limited amounts of data available for most Indigenous languages, especially for endangered ones, the development of translators for such languages is only feasible today due to recent developments in AI technology, such as the use of Transformer technologies and the availability of open pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs). Our team has focused not only on overcoming the associated technical challenges but also on making sure that the technology we create is useful and supports the needs of Indigenous peoples, what we are accomplishing by trying to work as much as possible directly with them.

Usually machine translators for low-resource languages such as endangered Indigenous Languages involves taking generic LLMs, pre-trained on large corpus using self-supervised techniques with high levels of data, and fine-tune them with a much smaller parallel downstream corpus in the target language. Additionally, some works suggest translation quality is improved by using multilingual models. However, our experience in building translators for Indigenous languages has led us into a different direction. In our experiments, by analyzing the results of experiments creating bilingual and multilingual translators for 39 Brazilian Indigenous languages, using Bible data, we saw that multilingual translators often achieve falsely improved accuracy results by adopting a "cheating" strategy of memorization.

Therefore, we have based our development on bilingual translators. We have also found that the most significant improvements in accuracy were obtained by manually enhancing the quality of the fine-tuning training data used to create bilingual translators. These results were further validated through a manual evaluation of the effectiveness of a translator for the Nheengatu language. By doing this, in initial experiments, using manual evaluation of the outputs, we have observed that about 65% of about 200 test outputs produced were perfect or mostly correct, despite being trained with only about 6,200 pairs of sentences, extracted mostly from dictionaries, lexicons, and bilingual story- and textbooks.

These results suggest that it is feasible to fine-tune LLMs into valuable bilingual translators using data commonly available for Indigenous languages that have been reasonably documented and studied by linguists, if some key methodological conditions, such as data cleanliness, are met. The translators were deployed as API-based services and had an average response time of 1-2 seconds, which was found adequate for the task.

SPELL CHECKERS AND OTHER TOOLS

The main tools we have been building are:

- Word dictionary: a tool to provide access to words, their meanings, and translations based on approximate search;

- Word completion: a tool which suggests words which can complete a partially-typed word;

- Next word completion: a tool which suggests words following a completely typed word;

- Spell checker: a tool which suggests corrections in the words of a partially- or a fully-typed sentence.

The word dictionary used in Nheengatu prototypes was implemented by looking up a database of words extracted from actual dictionaries available for the language. This database contained associated descriptions in Brazilian Portuguese and English for each word. One shortcoming of that version was not listing valid variations of base words, such as the use of prefixes and suffixes to indicate gender, number and verbal tenses. Most digital dictionaries for major languages used in editing tools often incorporate the handling of variations by directly programming rules by hand, a time- and effort-consuming process. We believe this can also be achieved by training an LLM with appropriate synthetic data, an idea yet to be verified in practice.

The word completion word completion tool used in the Nheengatu prototypes used a variation of the techniques used by the word dictionary, based on partial searches in the database of words. Partially-entered words were matched against the list of valid words and the most likely words were listed in alphabetical order.

The next-word completion tool used in Nheengatu prototypes have been implement as a bag-of-words machine learning model, trained with sentences extracted from the bilingual datasets created for the training of the translators. Next-word completion is a task extremely dependent on the context and good performance is often achieved through personalization, that is, on learning the most commonly used words by an individual. In this initial version, however, we focused on a general-purpose training set where we decomposed the original sentences in sub-sentences with up to five tokens, and used the subsequent token as the label to train an SVM-based classifier. At runtime, when the user types in the writing assistant, the system sends the typed words to the classifier and which suggests the next word.

We deployed an initial spell checker tool in the Nheengatu prototypes developed using an LLM-based framework, but focused only on special markers of tonicity. The basic idea is to first generate a dataset with pairs of correct and incorrect sentences, where the incorrect versions are created synthetically by changing, removing, or adding letters, following common human patterns of producing typos. We first implemented this methodology with a dataset in Portuguese language, where we obtained an accuracy of about 60.8%. We are currently in the process of applying the same methodology to Nheengatu, using sentences extracted from the bilingual datasets created for the training of the translators, as we did with the next-word prediction tool.